Individual stocks instead of ETF: Simple Strategy for Investing in Stocks

Individual stocks offer returns far beyond the approximately 10 percent provided by ETFs and the like. The question is, which stocks? It’s clear that not all stocks worldwide perform well. So, how do we select the stocks that can earn us more in the long run than popular world ETFs, the S&P 500, and the Nasdaq 100?

Note 1: We do not guarantee that you will outperform index funds by following the tips in this article. However, we believe it to be “possible to very possible.”

Note 2: Due to their volatility, individual stocks are especially suitable for young people. As you get older, assets should increasingly shift from individual stocks to stock funds, bonds, and real estate.

As the first step in our stock selection strategy, it’s a good idea to examine the index funds mentioned above and consider whether we want to act similarly with our own small DIY ETF:

Omitting Stock Weighting in the Portfolio

Index funds use weighting, but we want to omit it.

Weighted Composition

The composition of most index funds is weighted according to market capitalization, i.e., the total value of each company’s stock.

As of August 2024, Apple, Microsoft, and Nvidia each reach a market capitalization of 3 trillion EUR, while companies at the bottom of the S&P 500 list have less than 10 billion, or about 0.3 percent of that amount.

This gives large companies a much greater influence on the price development of the respective index fund than smaller companies.

This has theoretical pros and cons. Large companies tend to weather difficult phases better, as they have greater resources and are more likely to receive help from external actors (banks, government) (“too big to fail”).

On the other hand, it’s obvious that a very large company has less growth potential than a smaller company.

Large companies in an index fund theoretically stabilize the fund’s price but also reduce returns.

That’s the theory. In practice, even giants like Apple seem to keep growing, and at a company value of 3.5 trillion EUR (as of August 2024), there seems to be no end in sight.

This raises the question of how this is possible. Apple has tripled in a relatively short period without bringing groundbreaking new products to the market.

This seemingly contradictory development is mainly due to the current hype around artificial intelligence and the fact that stock price development and actual economic development do not necessarily correlate.

Regardless of real economic development, there is a powerful, parallel, and quite linear phenomenon:

The accumulation and concentration of wealth through inheritance. In Germany alone, an estimated 500 billion EUR is inherited annually. To our knowledge, there is no country worldwide where inheritances are taxed at standard rather than reduced rates.

In Germany, only about 7 billion, or just 1.5% (!) of the total inheritance volume, ends up with the state – the rest goes to the recipients.

This rapid accumulation of wealth compared to labor income happens worldwide. A slowly growing number of heirs accumulates more and more wealth, then seeks investment opportunities.

“Money in search of investment opportunities” is thus a strong driver of stock prices alongside economic development and is partly responsible for why even supposedly “mature” companies like Apple continue to grow like a startup.

Here, it’s more about the money looking for a safe and profitable harbor, finding Apple among others, than Apple attracting the money through its economic activities.

Stock Buybacks as an Additional Price Driver

Another factor driving up stock prices is the increasingly popular stock buybacks by companies themselves.

This method of price management is particularly popular among U.S. companies.

“Money Printer Go BRRRRR”

The above title is an internet meme (a cultural phenomenon) that mocks central banks and their money-printing machines, which (allegedly carelessly and endlessly) print new money, with the machines making a rattling sound (“Brrrrr…”).

The seemingly humorous meme criticizes central banks, showing that the central banks’ process is trivial: “starting up the money machines,” while consumers face rising prices and can’t simply push some buttons.

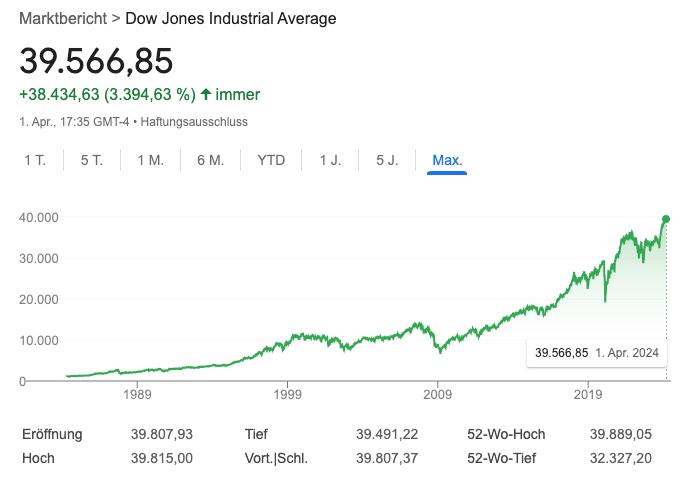

The ongoing increase in the money supply through fresh money printed by central banks and the inflation that results from it is arguably the main reason for ever-rising prices.

As money loses value, investors have no choice but to invest it as profitably as possible to at least offset the value loss due to inflation.

No Weighting in Our DIY ETF

For practicality and because we think we don’t need it, we do without weighting.

Weighting is impractical for our needs because:

- …we want to hold dozens of stocks for diversification

- …stocks have very different prices, ranging from double to four-digit values.

- …we want to buy whole shares instead of fractions, as is possible, for example, with TradeRepublic, to reduce potential delays or other problems with the transfer of individual shares or the entire portfolio (although share fractions would make it easier to keep our stock packages at the same value)

Creating dozens of packages (“positions”) of whole and differently priced stocks already requires somewhat larger investment sums. For example, if you want to buy a stock that costs 1,500 EUR, you would have to increase all other 20-40 packages to about 1,500 EUR to keep the packages roughly the same value.

If you also wanted to weight as ETFs do, the required investment amount would be even greater. For Apple, with over 3 trillion EUR market cap, you would need 100 times as much as your smallest company with a 30 billion market cap.

If the smallest company’s stock in your portfolio costs 200 EUR, you would need to hold Apple at 20,000 EUR with proper weighting and nearly as much in Microsoft and Nvidia.

Besides weighting by market cap, which most ETFs use, and our principle of keeping stock packages approximately the same value, there are other approaches:

- “Buy the dip” method: You add to stocks that have recently weakened whenever you have fresh investment funds (e.g., salary entry). We also apply this method in practice with the “even distribution” principle. Since we usually don’t have enough fresh money to top up all 20-40 stock packages at once, we sensibly buy stocks whose price isn’t at an all-time high (ATH or “All Time High”) if possible.

- “Fluctuating weighting” method: You weight freely or according to your own principles, readjusting periodically, for example, based on market conditions or current company assessment

- A frequently cited author considers the “weighting by GDP of the country where the company is located” method better than classic market cap weighting. Looking at the data of interesting companies, however, shows that they are all in the same country: the USA. The GDP of other countries is irrelevant, in our view.

We don’t need weighting for safety reasons, because:

- …we limit ourselves to companies with a minimum size (at least about 30 billion in market capitalization)

- …we limit ourselves to companies with a history of high annual returns

- …we limit ourselves to companies from the Anglo-Saxon and EU area, as ETFs often do

We thus consider each of our 20 to 40 stock packages (= companies) an equal ticket and assume that 30 billion in market capitalization, combined with a long history of returns and a location in the US/EU, makes a company stable enough to be on par with Apple & Co. in our portfolio.

If we invested billions like the large ETF providers, we would also weight to avoid influencing the price with our investment.

But this risk of price influence doesn’t exist with our comparatively small stock packages, each up to six figures. Example: 25 companies’ stocks at about 1,000 to 100,000 euros each.

Instead of weighting, we build – for diversification purposes – a sufficiently large number (20-40) of stock packages of different companies, each with approximately the same value.

We distribute fresh investment funds across our 20-40 stock packages to keep them roughly equally valuable. Not every company is included each time, as with 2,000 EUR in fresh money, you can’t buy 30 different stocks if some of them already cost 700 EUR or 1,500 EUR per share.

Number of Companies in ETFs

Professional ETFs contain 100 to more than 1,000 companies. For practical reasons, we limit ourselves to around 20-40, as we did with the omission of weighting.

We don’t believe that private investors should ever have a three-digit number of different companies in their stock portfolio. It becomes too confusing and seems unnecessary in terms of diversification.

As diversification increases, returns decrease. The poorer-performing stocks in the portfolio drag down the overall return.

Therefore, to minimize risk, we want more than just a handful but not an excessive number of positions (companies) in the portfolio.

Company Size in ETFs

In the S&P 500, the smallest companies are worth about 7 billion EUR. In the Nasdaq 100, the smallest companies also have a single-digit billion value.

We limit ourselves to companies with at least around 30 billion EUR in market capitalization. This is a figure we didn’t just think of in advance; instead, we first looked at the current company values to decide where we could reasonably draw the line.

So we set the rules after we got an overview of the situation, which is the right approach.

We set the “minimum company size” requirement because large companies tend to be more viable and less prone to manipulation. Government aid, bank loans, or recovery on their own are more likely the larger the company.

It’s also much harder for external actors (hedge funds, billionaires, banks) to manipulate the price of large companies to their advantage.

Since we ultimately want to select 20 to 40 companies and want the pre-selection to be slightly larger than that, we first had to check at what minimum size we still have enough options.

At the NYSE (New York Stock Exchange), there are about 300 companies with a value of at least 30 billion, and on the Nasdaq, there are 90 companies.

With the above guidelines (Min. 30 billion market cap, listed on NYSE or Nasdaq), we can now select our 20 to 40 from more than 300 companies.

NYSE & Nasdaq instead of DAX

According to Google, the following company names and sectors or themes are most often searched in Germany in combination with the word “stocks,” sorted by frequency:

- Hydrogen

- AI

- Dividends

- Cannabis

- Nvidia

- Lithium

- Daimler Truck

- DAX

- Uranium

- Bayer

- Tesla

- Rheinmetall

- BASF

- Amazon

- Siemens

- Birkenstock

- VW

- Gamestop

- Paypal

It’s clear that many private investors’ stock choices begin with brainstorming company names and familiar brands rather than research. You might think of “Porsche” because of great cars, or “Cannabis” because it’s newly legal, or “Rheinmetall” because of the Ukraine war.

The criteria “good product,” “familiar brand,” and “positive environment” apply to most high-return stocks.

But the reverse isn’t true: Many companies meet the above positive criteria (product, brand, environment). Yet the stock prices of these companies rise relatively slowly.

We will also look at what the company actually does, but only on a very superficial level and afterward. First, we make a pre-selection based on the stock prices of the past 10 to 30 years.

It’s often said that you can’t deduce future performance from past performance.

But looking at historical price development is the best tool available to us.

We make our pre-selection based on stock prices from the last 10 to 30 years.

From this list of top stocks, we manually remove companies whose future we view critically.

Since we have a larger selection, we can afford to do without some stocks or entire sectors.

Always Buy, Never Sell: Buy and Hold

Less is more: Trading stocks is time-consuming and frustrating. The stock market is highly professionalized and filled with terminology, virtual constructs, and complex regulations.

The plan to capture more than the usual price movement as a private investor is very ambitious against this backdrop.

Day trading can make some profit, but the time commitment, emotional strain, and the fact that you hardly learn anything or have any skills to show years later make it overall very unattractive, and we strongly advise against it.

Therefore, we only buy and never sell. Aside from the fact that taking profits often doesn’t pay off because the price rises further afterward, and you miss out on these gains:

Selling is a taxable event, and capital gains tax is deducted where applicable. The money you pay as capital gains tax could have continued to work and earn returns.

Buy and Hold performs very well in the long run and creates minimal stress or time commitment. We also want to delay any tax payments as much as possible, similar to the tax deferral effect of asset management GmbHs.

Time in the market beats timing the market

This stock market wisdom suggests that you end up better off if you let stocks sit long-term (“time in the market”) rather than trying to predict prices (“timing the market”).

“Timing the market” is the modern version of the alchemist’s quest for the “philosopher’s stone,” which could turn base metals into gold and silver.

Example: You observe that your – very individual – stock portfolio as a whole climbs about 2% above the initial value during the day and falls up to 2% below the initial value by the evening for several days.

This makes it tempting to sell everything at noon or in the afternoon to buy it back cheaply in the evening. You would then have earned 2 or 3 percent in one day.

That works with some of your stocks, and you make 10 EUR here, 50 EUR there, or correspondingly more if your positions are larger. Some of the stocks barely move that day, so you don’t sell them. So far, so good.

But with one stock, you don’t get back in. After selling it at noon, it keeps rising. You hope it might drop the next day, but it keeps going up.

Now you have opportunity costs: You aren’t benefiting from these stock price increases. If you hadn’t traded but just held on, you would have earned more with less time and stress.

Finally, you repurchase this stock, which you sold for profit-taking and intended to buy back cheaper, at a significantly higher price a few days later.

You want to hold this stock long-term, and since it’s unlikely to fall below your selling price from a few days ago, you have no choice but to accept the higher price.