Art as an Investment – Are Paintings and Sculptures Sensible Investments?

Art is fascinating— aesthetically, culturally, and sometimes financially. But “art as an investment” is not a stock-market product; it is a market with its own rules: opaque, fragmented, and heavily dependent on taste, provenance, and timing. This article explains how returns in art arise in the first place, why pricing works the way it does, which risks (and costs) many people underestimate—and what options exist even for small investors.

What does “art as an investment” mean—and what doesn’t it mean?

When people talk about art as an investment, they usually mean capital appreciation (capital gains): a work is bought today and sold later at a higher price. Unlike stocks, there is no dividend, no ongoing coupons, and no standardized market price. Instead, value depends on a bundle of factors such as rarity, condition, provenance, exhibition and publication history, market trend, and—last but not least—the story that can be told around the work.

At the same time, “investment” in art is often closely tied to collecting motives: people buy not only for returns, but also for pleasure, status, cultural capital, or as an identity marker. This “non-financial dividend” can be very real: if you love a work, it is easier to hold it for longer—and that matters because the art market rarely offers quick liquidity.

Many wealth managers emphasize that, alongside opportunities, there are ongoing costs—such as storage, climate control, and insurance. These “carry costs” help determine whether an investment ends up truly delivering strong net returns.

How prices are formed in the art market: auction, gallery, private sale

Art is traded in two broad “worlds”: the primary market (first sale via a gallery/artist) and the secondary market (resale, e.g., at auction). In the primary market, prices are often “set”: galleries manage availability, place works with collectors, and try to build a market in a controlled way. In the secondary market, prices become more visible—but also more volatile: auctions create public reference points, yet not every auction is representative—one bidding war can push prices upward, and lack of interest can lead to a “bought in” result (unsold).

Why “transparency” is such a big topic in art

A large share of turnover happens through private deals. Even at auctions there are often guarantees, third parties, irrevocable bids, or discreet arrangements. This makes price discovery complex. Resale data (“repeat sales”) is therefore popular in research: it compares the same work across different years—and offers a more realistic view of returns because it doesn’t look only at “trophy records.”

Typical costs investors should factor in

| Cost item | Where does it occur? | Typical magnitude (rough) | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auction premium / Buyer’s Premium | When buying at auction | Several percent up to double digits, depending on the auction house & price tier | Raises the entry price immediately—acts like a “spread.” |

| Seller’s commission | When selling (auction/private) | Negotiable; can also be several percent | Reduces the exit proceeds—critical when appreciation is only moderate. |

| Transport & handling | Both directions | Depends on size, insurance, customs, risk | Can be significant for international purchases. |

| Insurance & storage | Ongoing during the holding period | Annual; depends on value, location, security | Carry costs reduce net returns—especially over longer holding periods. |

| Expert opinions, authentication, restoration | Before purchase / in case of issues / before sale | From moderate to very high | Can preserve value—or uncover risks (forgery/misattribution). |

Tip: If you compare returns with stocks, calculate net of costs. Art often has higher transaction costs than liquid financial markets, which raises the hurdle for “good” performance.

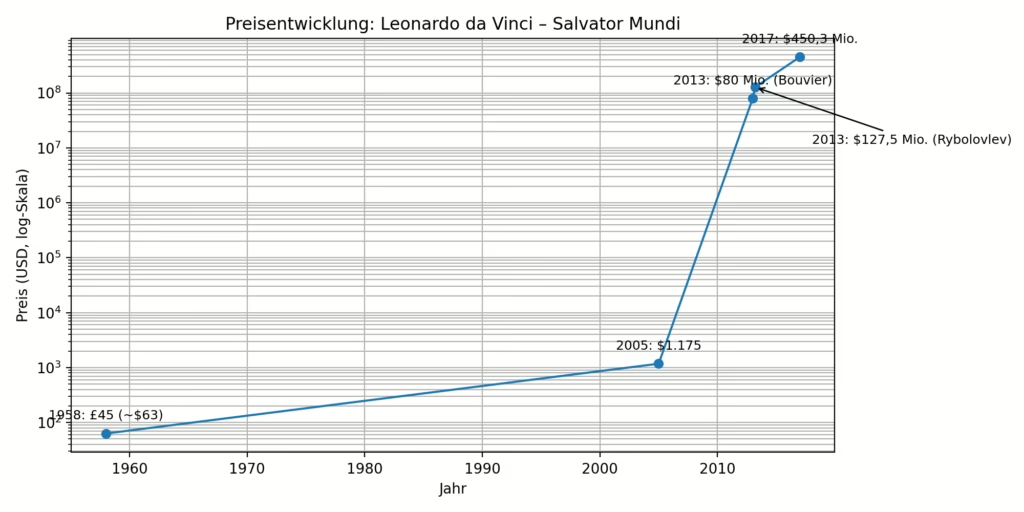

A concrete price trajectory: “Salvator Mundi” (Leonardo da Vinci)

To make tangible what “price development” can mean in art, it helps to look at a prominent work with documented resales: “Salvator Mundi”, the painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci that achieved a record price at Christie’s in 2017. The case is extreme—but instructive, because it shows how attribution, story, scarcity, and marketing can drive value.

Selected known transactions (nominal, in USD where stated)

- 1958: Sold at Sotheby’s for £45 (then listed as the work of a pupil).

- 2005: Bought at a regional U.S. auction for $1,175, catalogued as “After Leonardo.”

- 2013: Sold for $80m to a company controlled by Yves Bouvier (private sale).

- 2013: Resold for $127.5m to Dmitry Rybolovlev (private sale).

- 15 November 2017: Auction at Christie’s New York: $450,312,500 (incl. Buyer’s Premium).

The chart below visualizes this trajectory. Important: the jumps are so large that a logarithmic scale makes sense—otherwise the early portion would be barely visible.

What we can learn from the “Salvator Mundi” case

- Authenticity/attribution can be a value driver—and a risk: if expert opinion shifts, market value can suffer dramatically.

- There is no automatic liquidity premium: even extremely expensive works can remain “invisible” for a long time after purchase.

- Private sales are opaque: the 2013 prices are known, but details on terms/fees are typically not public.

- Marketing matters: Christie’s placed the work in a Contemporary sale and staged it globally—this can generate demand.

More prominent examples: the same work—later more expensive (or with risks)

Do “trophy assets” (top objects in the multi-million range) have relatively stable value development? This intuition is widespread—and market data partly supports the idea that the very top end is often more resilient than the middle. At the same time, repeat-sales studies show that losses are common and that “art returns” can vary widely by period, segment, and methodology.

Examples with publicly reported resales

| Work | Earlier purchase | Later sale | What does it show? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gustav Klimt: “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II” (1912) | 2006: $87.9m (Christie’s; buyer Oprah Winfrey, reported) | 2016: $150m (private sale, reported) | An example that “blue-chip” art can appreciate strongly over 10 years—net results still depend on costs/taxes. |

| Leonardo da Vinci (attributed): “Salvator Mundi” | 2005: $1,175 (regional; as “After Leonardo”) | 2017: $450.3m (Christie’s, incl. premium) | Extreme case: re-attribution, restoration, storytelling, and scarcity can make prices explode—but it’s not predictable. |

| Mark Rothko: “No. 6 (Violet, Green and Red)” | Before resale: reportedly about €80m paid by a dealer | 2014: reportedly €140m sold to a collector | Shows market mechanics: dealer margins/information advantages, opacity, and the risk of buying in too high. |

Note: for private deals, details (payment terms, fees, guarantees) are often unclear. For investment analysis, auctions are more transparent—but even there factors like guarantees and premium structures can matter.

Return, risk, correlation: what do studies and market reports say?

With art returns you have to look very carefully at how they are measured. A common approach uses repeat-sales indices (e.g., Mei/Moses), which include only works that traded at least twice. This reduces some biases, but it is not perfect: works that are never resold (because they enter museums or remain in family collections) don’t show up. Moreover, art markets are segmented: “Contemporary” behaves differently from “Old Masters,” and within any segment artists, periods, and specific bodies of work matter enormously.

A few robust observations

- Over the long term, art can perform moderately positively, but it is often described as less liquid and more expensive to trade.

- Diversification: several analyses discuss relatively low correlation with traditional assets—though the data is thinner than for stocks/bonds.

- More recent phases can also be weak: some newer evaluations and market commentary point to weaker returns and/or high dispersion in recent years.

“Top end vs. the rest” — why trophy works often appear more stable

Market reports (e.g., Art Basel & UBS) regularly describe how the art market’s top end is dominated by a small number of extremely sought-after names. Buyers compete globally, supply is scarce, and prestige effects are strong. This can create a kind of “quality premium.” But: even trophy art is not immune to shifts in taste, reputation damage, authenticity debates, or liquidity bottlenecks when many want to sell at the same time.

What investors often underestimate

- Illiquidity: a “fair price” is often achievable only if you have time (and the right channel).

- Risk concentration: a single work is a concentrated bet. Even blue-chip artists can be cyclical.

- Net return: after premiums, commissions, storage, and insurance, the math looks different.

- Information asymmetry: professionals know more (or have better networks)—especially in private sales.

Is art suitable for small investors?

Yes—but rarely in the way the headline “art as an investment” suggests. If you enter with a limited budget, you can still participate meaningfully, but you should accept different goals and rules: less “beating the market,” more learning curve, enjoyment, and risk management.

Four realistic paths for small investors

- “Buy what you love”—but with a system: Instead of speculating on quick wins, buy into niches you understand (photography, editions, local scenes). A long-term collection can build value—and even if it doesn’t, the utility remains (aesthetics, culture).

- Editions/prints/photography: Editions are more accessible, but price development depends heavily on edition size, signature, condition, and market demand. Research is often more important here than budget.

- Fractional ownership / platform models: Models like “shares in a work” lower the entry barrier, but they don’t remove the risks. Pay attention to the structure (e.g., special-purpose vehicle), fees, holding periods, tradability of shares, and the fact that past performance is no guarantee.

- Indirect exposure: If you want art-market exposure but don’t want storage/authenticity risks, you can also think indirectly (e.g., companies in the art ecosystem). That is then more of a classic equity play than “owning art.”

Practical checklist for getting started below the million-euro league

- Provenance & documentation: keep invoices, certificates, edition info, exhibitions—collect everything.

- Condition: condition is price. Small damages can make resale much harder.

- Comparable prices: if possible, compare auction data/marketplaces; beware of dealer “asking prices.”

- Channel strategy: where would you sell later—auction, gallery, private? Each channel has different costs/opportunities.

- Budget for ancillary costs: framing, transport, insurance—this is where people often “forget” to calculate with smaller works.

Common assumption: “Only top objects are relatively safe”—is that true?

This assessment is understandable: the market can look “barbell-shaped”—very strong demand at the very top, and a lot of uncertainty below. Market reports in recent years often emphasize that the highest price tier is carried by a small number of names and very scarce works, while mid-tier segments can fluctuate more.

Still, a nuance matters: safety is not guaranteed even at the top. Trophy works are more expensive, but not automatically more liquid—on the contrary, the buyer pool is smaller, and the “right stage” is crucial. And a work below the million level can perform relatively well if you truly understand the field (artist career, curatorial attention, museum acquisitions, critical reception).

A pragmatic view

- Top objects often have better market infrastructure (advisors, guarantees, global buyers)—this can provide stability.

- Below that dispersion is larger: you can find both “10x” stories and quiet value erosion.

- Know-how can create more edge in the mid/low end than at the top, where every professional is bidding.

Art can be an investment—but rarely an “easy” one

Art as an investment works best if you don’t treat it like a stock. The big wins often come from a combination of knowledge, access, timing—and luck. At the same time, art can be a sensible component if you accept its specifics: high transaction costs, illiquidity, information asymmetries, but also the possibility to “consume” cultural and emotional value while you hold.

For small investors, the most realistic approach is often: start small, take documentation seriously, calculate ancillary costs, and invest more in learning + network than in “the quick flip.” And if you do prioritize returns, it’s often smarter to think diversified and structured—while keeping a very clear eye on fees and liquidity.